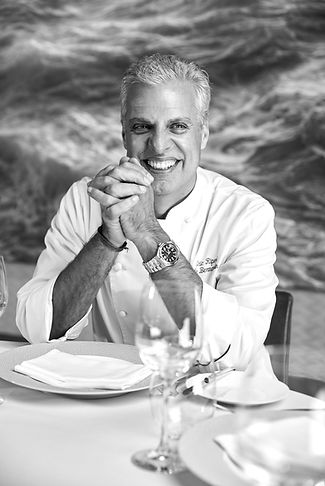

Eric Ripert (Le Bernardin): Humble perfection

Enrolled in hotel school at the age of 15, Eric Ripert began working at La Tour d'Argent and Jamin with Joël Robuchon at a very early age. He moved to Washington in 1989 to work at Jean-Louis Palladin's Watergate, then moved on to David Bouley in New York in 1990 before joining Gilbert and Maguy le Coze at Le Bernardin in 1991. When Gilbert died in 1994, he took over and reached heights that he has maintained for 30 years now.

Where do you find your inspiration?

I live in New York. It's a privilege to live in a city where people from all over the world come together. It's a real melting pot of cultures. We're constantly discovering new flavors, ingredients, and techniques. And we live well and travel, so we can go to the source of each culture.

You change the menu constantly. What was your latest creation?

It was yesterday. We combined a chawanmushi technique with Italian and Spanish ingredients: gamberoni, barnacles, and razor clams. The dish was finished off with a lobster consommé with Thai spices and shrimp head tempura. It's a dish that brings together all my experiences. If my restaurant were in Brittany, the result would undoubtedly be more Breton.

When will this dish be on the menu?

It was added to the menu today. We tested it yesterday with around fifty customers. And since they liked it, we added it. It's a very collaborative process. The whole team questions itself. Everyone puts their ego aside. At Le Bernardin, this type of constant innovation is part of our culture.

Speaking of culture, how does the United States differ from Europe?

First of all, I think there are some misconceptions in Europe: I often hear people say that the US lacks good products or good food. I had the same preconception when I arrived, and I was surprised to discover, alongside Jean-Louis Palladin, that the opposite was true: Maine eels, Carolina pufferfish, and California oysters. Most chefs here are extremely talented. I assure you that America is not just a country of burgers. Compared to Europe, we operate in a very healthy competitive environment. We chefs are friends, we help each other, but the environment is very competitive. No one would dare rest on their laurels. Here, risk-taking is part of the game. And then we have critical mass! 15,000 employees work in the building above us, and New York customers are educated, have the means to treat themselves, and have a good understanding of the experience we offer them.

And in terms of the restaurant's organization?

180 people work at Le Bernardin between the dining room, the kitchen, and administration. We enjoy a very good atmosphere between the dining room and the kitchen, whereas in my youth, I remember constant tensions at this level in France.

You have had three Michelin stars since the guide began in New York and four stars from the New York Times since 1995. How have you managed to maintain this level of excellence for three decades?

I am very disciplined. I get up at 6 a.m. every day. I meditate. I study Buddhist scriptures. I perform a few rituals in a meditation room at home. This usually takes me 90 minutes. Then I spend time with my family. And I walk to the restaurant through Central Park. I don't go out during the week. I don't overindulge.

©NigelParry

"Everyone creates their own luxury."

©NigelParry

Maguy le Coze

"Everyone should ask themselves what they don't like doing."

So it's a question of balance?

Absolutely. I divide my day into three parts: one third for the restaurant, one third for my family, and one third for myself. I go on retreats where I don't have a phone or internet connection. This model works very well for me. I feel focused, I have all my energy, and I get good results at work and with my family. When I'm alone, I feel like I'm on top of a mountain: the restaurant supports my family. My family supports the restaurant. Being able to take a step back, alone, is a great luxury. But in reality, everyone creates their own luxury.

©DanielKrieger

What lessons can you share?

I think it's essential to have as clear a vision as possible in the short, medium, and long term. I always ask myself where I want to be in three years, in ten years, and what my ultimate goal is. This allows me to channel all my energy into achieving the desired result. I am fortunate to have known from the age of five that I wanted to become a chef with a good team to offer a distinctive experience.

What would you say to those who say that young people today are faced with too many choices?

You have to manage your choices. I have always had a passion for cooking, no doubt because of Paul Bocuse. I loved to eat. I read his books. I had “the calling.” Everyone has to ask themselves what they like to do and, above all, what they don't like to do. This means getting to know yourself. I think the key is to dare to take the plunge without fear of failure. It's always possible to change direction later on.

You also support City Harvest. Can you tell us a little about this organization?

Yes, it's a very efficient organization that distributes food that would otherwise go to waste even though it's perfectly fresh. We collect it and distribute it to 400 food shelters across New York. We have 24 trucks and the City Harvest warehouse takes up an entire block in Brooklyn. We are in contact with restaurants, supermarkets, and farmers. Sometimes we collect unsold items, but in other cases we take boxes with labels that are simply illegible. In the United States, 40% of the food produced is unsold. I am very proud of the work we do.

A word about philanthropy. You support Tibet, for example. Have you ever been pressured about this?

No, never. No problems in China, for example.

A sensitive topic in restaurants is work-life balance. How do you adapt?

In the US, it's not really an issue, but in Europe—even though things have changed—I think the culture is unhealthy. It's too brutal and allows for too much stress. If you compare it to FedEx, those guys have to transport a package from one end of the world to the other in 24 hours, but there's no abuse or angry bosses. In France, chefs were little dictators. Some glorified anger. That's not good. Our industry needs to evolve. It's possible to achieve excellence by inspiring, not humiliating or terrorizing. Believe me, a chef who trembles makes his sauce less effectively. I try to use my credibility to communicate on this subject with the media.

©NigelParry

If you want to learn more about City Harvest, click here!